Architectural Triumph, Engineering Failure

Berlin’s new airport was envisioned as one of the most advanced aviation hubs in the world — a facility worthy of a global capital. Designed by the renowned architectural firm GMP (Gerkan, Marg und Partner), the airport was meant to become both a symbol of modern Germany and a source of civic pride. Originally scheduled to open in 2011, it soon turned into one of the country’s most notorious construction stories — a monument to delays, engineering errors, and mismanagement.

TATLIN investigated the current state of Berlin Brandenburg Airport (Flughafen Berlin Brandenburg “Willy Brandt”), its long road to completion, and what might finally bring it to life.

Twelve years of construction

Located just eight kilometers from the existing Schönefeld Airport, Berlin Brandenburg was designed as a multimodal transport hub for the future — a large-scale “Air City” combining aviation with business, leisure, and public space. It aimed to include offices, hotels, entertainment facilities, and multimodal connections — a modern gateway city in miniature.

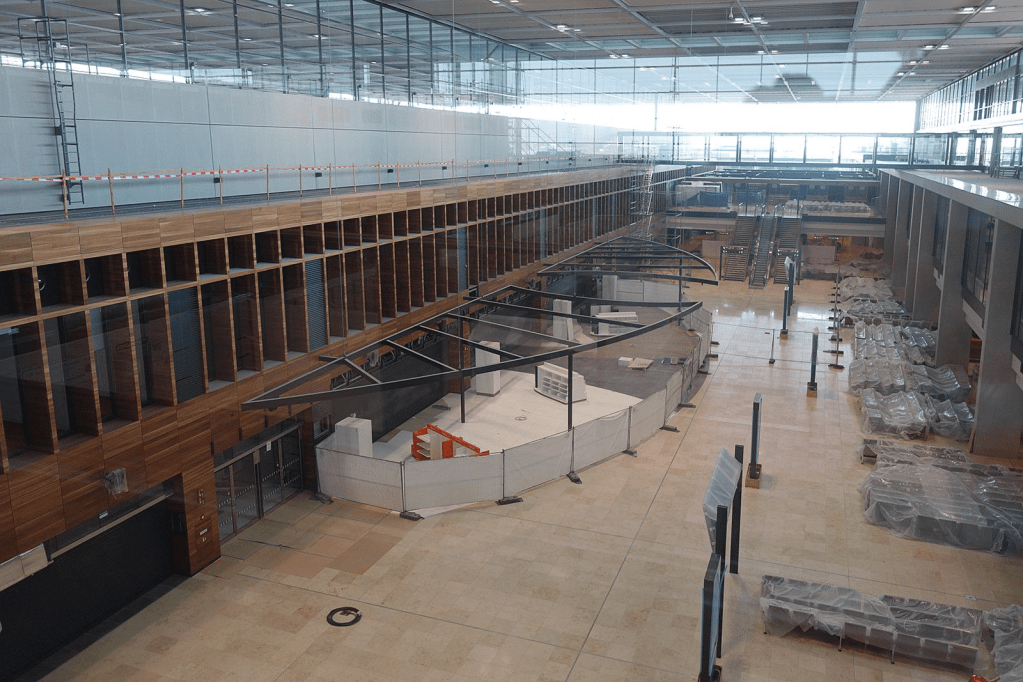

Today, the terminal building and part of its supporting infrastructure — including the rail station, hotel, and office blocks — are already completed. Yet the technical systems and engineering installations remain under constant revision and testing, becoming the primary reason for the endless postponements.

A perfectly built, unused space

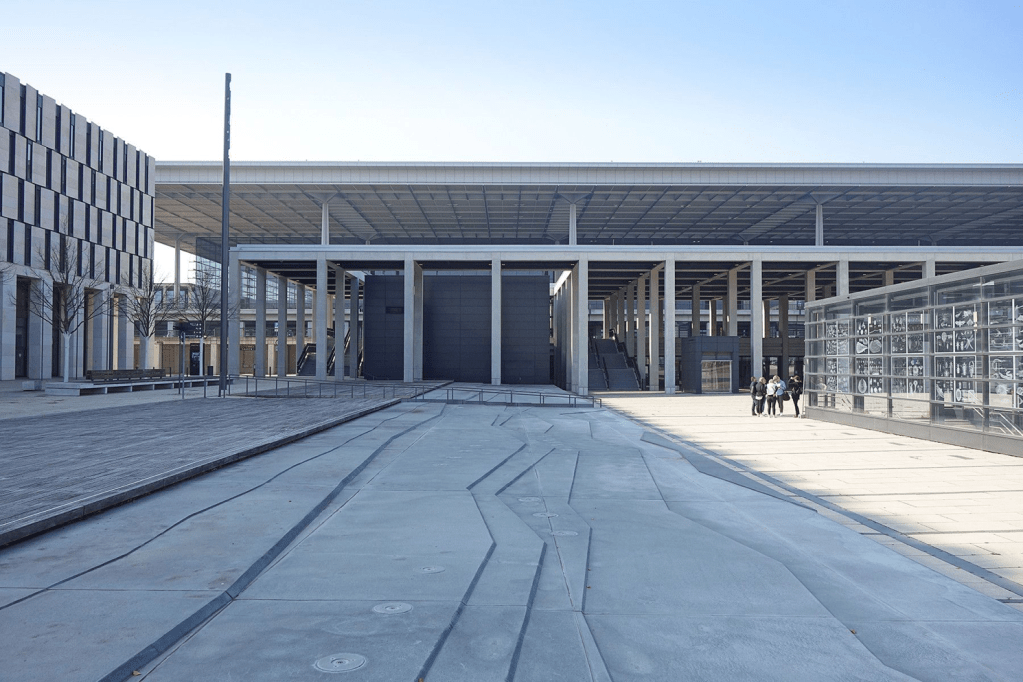

In front of the unopened terminal lies a central plaza, surrounded by office buildings and a hotel that has never received a guest. Some of the offices, initially intended for aviation-related or international companies, have been leased to unrelated tenants, such as medical organizations. Ironically, this plaza has become the only lively spot in the entire complex. It now serves as the starting point for guided tours, popular precisely because of the airport’s reputation as Germany’s most expensive construction failure. Driving schools use the vast empty space for lessons; photographers and journalists come for shoots, fascinated by the surreal atmosphere.

It is, indeed, an extraordinary sight: a nearly completed airport — built to the highest German standards of precision — perfectly maintained, yet unused. Signs of delay are subtle but telling: a small birch tree sprouting through the pavement, a dry fountain, and peeling decorative film on the glass exits of the underground station — reminders of a project that has stood still for years.

Fig. 1. View from the central square towards the terminal: hotel on the left, exit from the underground station on the right.

The station beneath the square

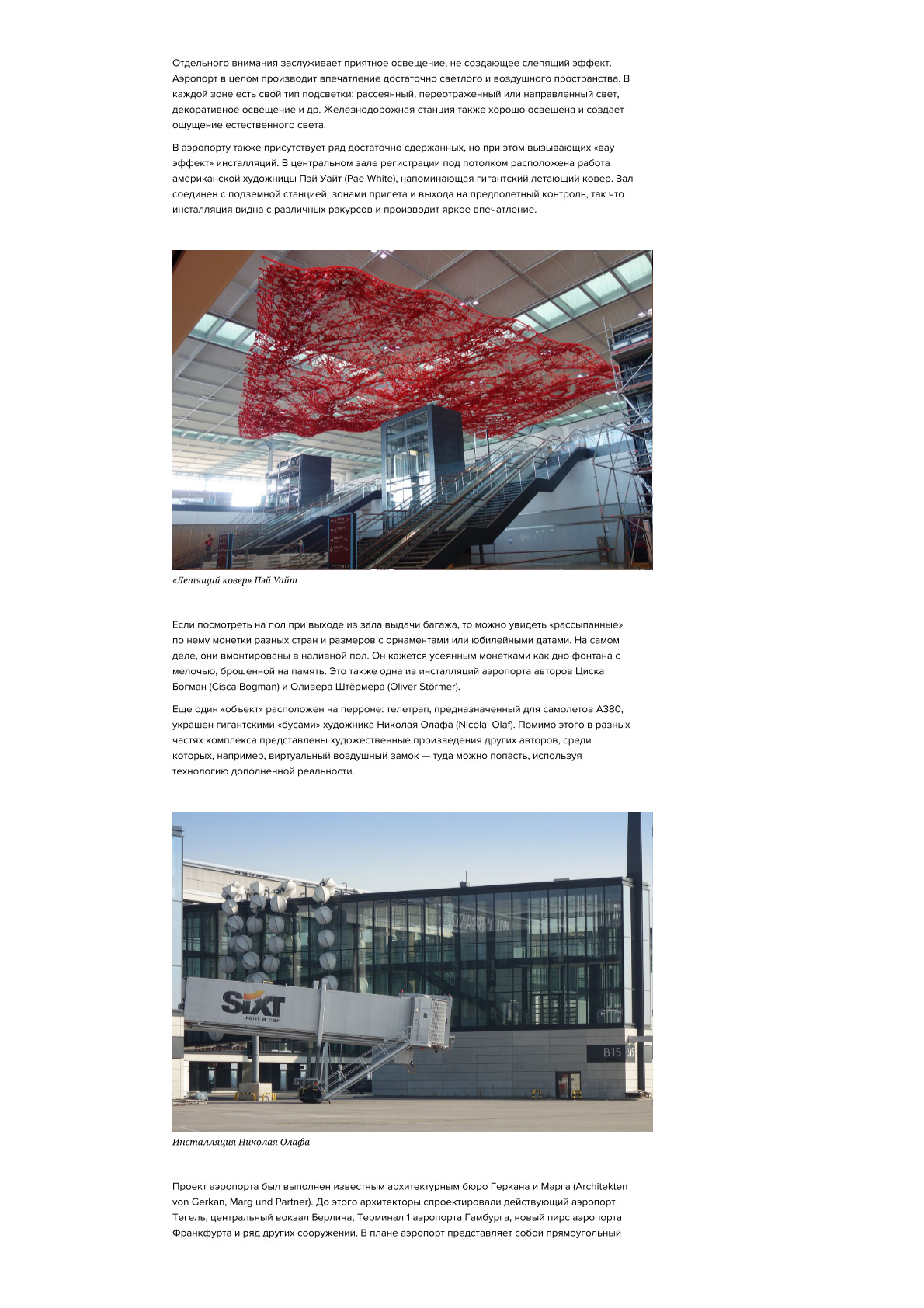

Directly beneath the central square lies the underground railway station, one of the first elements completed. To prevent the rails from rusting and to maintain air circulation, trains still arrive regularly — not with passengers, but simply to keep the infrastructure alive and avoid the buildup of moisture and mold.

Technically, this station can handle all types of German trains:

- the S-Bahn for local routes,

- the Regionalbahn for intercity connections, and

- the high-speed ICE trains, which can reach any part of Germany or neighboring countries.

Once operational, the journey from central Berlin to the Brandenburg terminal would take only 25 minutes — a level of convenience that remains, for now, hypothetical.

Fig. 2. Exit from the underground station to the central square.

Architecture and interiors

Architecturally, Berlin Brandenburg Airport expresses the qualities of German restraint and precision.

The design is minimalist, ordered, and elegant. Despite the ongoing construction, stepping inside the terminal gives one a sense of aesthetic satisfaction — every joint, skirting line, and material junction is executed with surgical accuracy.

The details are meticulous: flush-mounted skirting boards, perforated wood-effect panels, structural glazing, finely grained concrete, and polished natural-wood handrails. Wayfinding is clear, furniture is stylish and well-crafted, and even the metal mesh shutters of unopened shops look carefully designed.

The result is a coherent architectural experience, a testament to craftsmanship — even if the building itself still cannot fulfil its purpose.

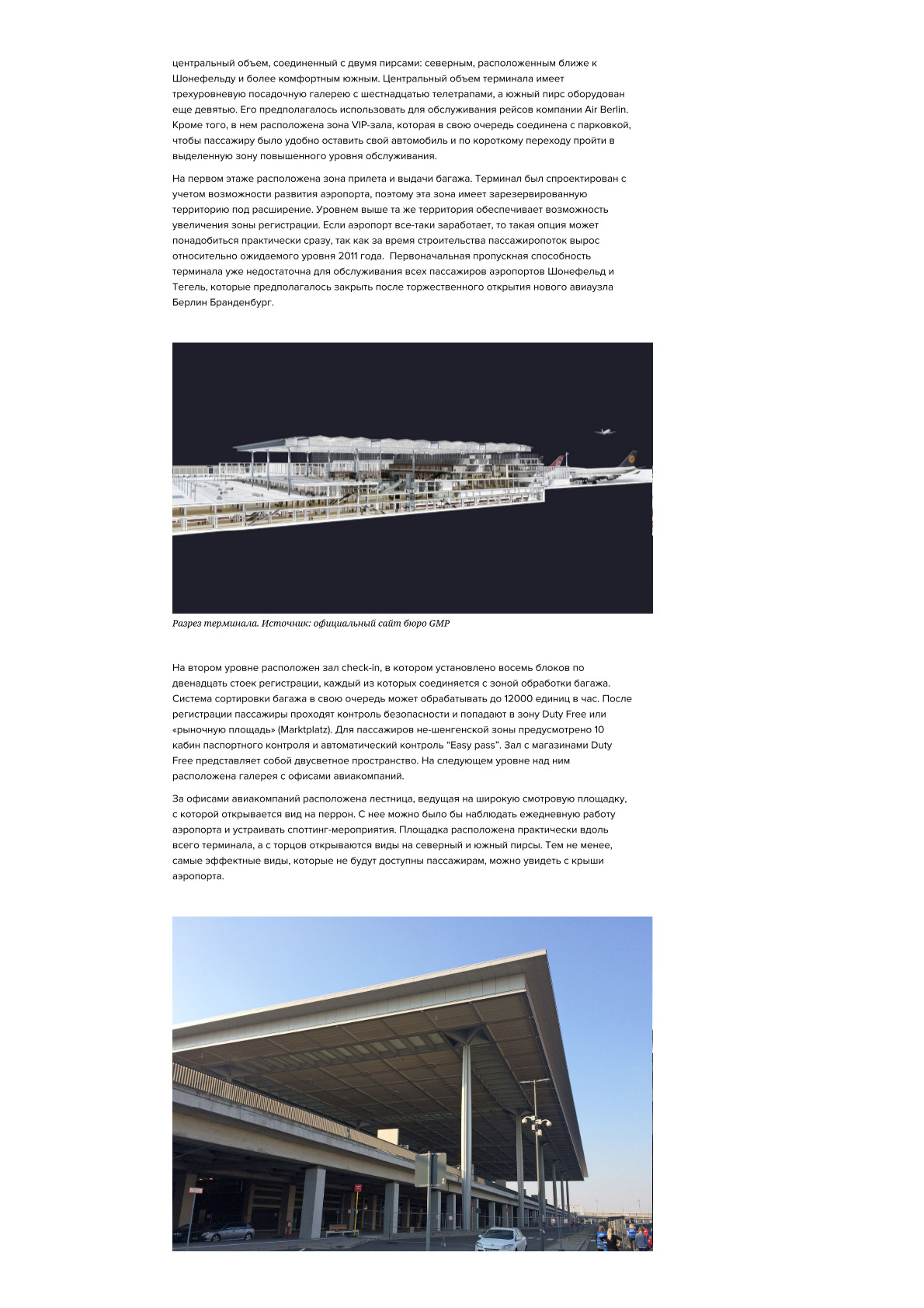

Fig. 3. Underground railway station

Light and art

The lighting deserves particular attention. It is bright yet never glaring, adding to the airport’s sense of openness and calm. Each zone features its own type of illumination — diffused, reflected, or directional, complemented by decorative fixtures. Even the underground station feels filled with natural light, creating a smooth transition between below-ground infrastructure and the main terminal halls.

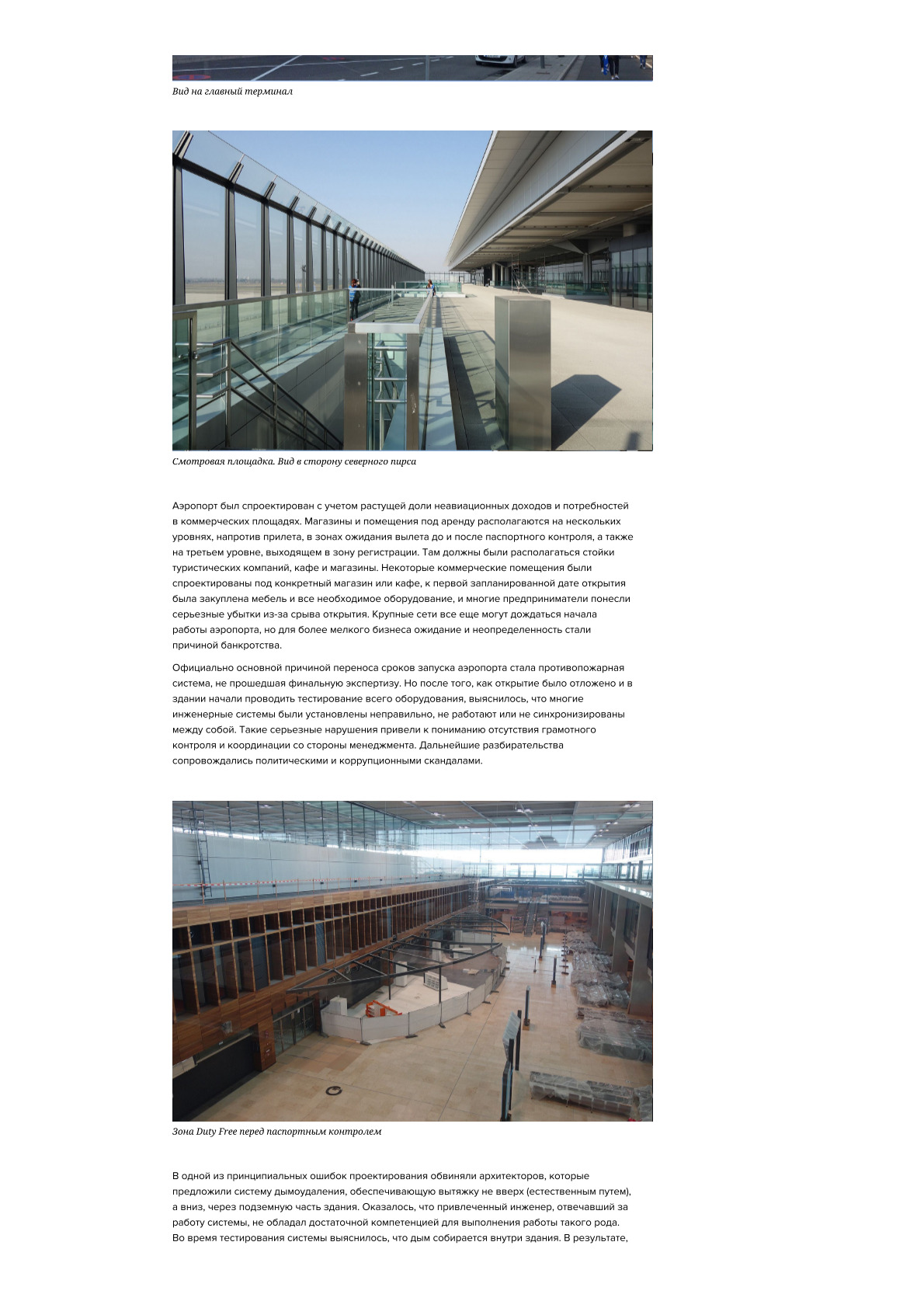

Despite its restrained architecture, the airport features several art installations that add a sense of surprise and emotional depth. In the central check-in hall, suspended from the ceiling, hangs an artwork by American artist Pae White — a massive, fluid sculpture reminiscent of a flying carpet. Visible from multiple levels — the underground station, the arrival zones, and the pre-flight security area — it creates a striking, almost surreal impression.

Fig. 4. Art installation “Flying Carpet” by Pae White.

If you look down while exiting the baggage claim hall, you’ll notice the floor scattered with coins of various sizes and origins — complete with national emblems and commemorative dates. They’re not accidental: each coin is embedded within the poured resin floor, evoking the image of a fountain filled with coins thrown for good luck. This installation, by artists Cisca Bogman and Oliver Störmer, transforms a transitional space into a quiet reflection on travel and time.

Another piece can be found on the apron, where the passenger bridge for the Airbus A380 is adorned with giant glass “beads” created by artist Nicolai Olaf. Elsewhere throughout the complex, other artworks appear — including a virtual “air castle”, accessible through augmented reality. These subtle interventions bring a sense of culture and imagination into what might otherwise feel like a monument to delay.

Fig. 5. Art installation by Nicolai Olaf.

Design and functionality of the terminal

The airport was designed by the acclaimed architectural firm GMP – Gerkan, Marg und Partner, whose portfolio includes Berlin Tegel Airport, the Berlin Central Station, Hamburg Airport Terminal 1, and several major extensions to Frankfurt Airport.

In plan, Berlin Brandenburg Airport consists of a rectangular central terminal connected to two piers:

- the northern pier, closer to Schönefeld, and

- the more spacious and comfortable southern pier.

The central terminal has a three-level boarding gallery with 16 jet bridges, while the southern pier adds another nine. It was initially intended for flights operated by Air Berlin and includes a VIP area connected directly to the parking facilities — allowing premium passengers to leave their car and walk straight into a private check-in and lounge zone.

On the ground floor lies the arrivals and baggage claim area. Anticipating future growth, the architects left reserved zones for expansion — both horizontally and vertically. Directly above, additional space can later be converted into an extended check-in hall.

This flexibility may soon prove necessary: during the long construction period, passenger forecasts have already exceeded the capacity planned in 2011. Once operational, the new airport will need to handle traffic previously shared by Tegel and Schönefeld, both of which were meant to close upon Brandenburg’s grand opening.

Fig. 6. Section of the terminal. Source: GMP Architects official website.

Passenger flow and check-In

On the second level, the check-in hall contains eight blocks of twelve counters each, connected to the baggage handling system below. That system can process up to 12,000 items per hour. After check-in, passengers proceed through security control to the duty-free zone — designed as a spacious market square (Marktplatz).

For non-Schengen travelers, there are ten passport control booths and automated EasyPass gates.

The duty-free hall is a double-height space, filled with light, with an upper gallery that houses airline offices.

Behind these offices, a stairway leads to a broad observation terrace overlooking the apron.

From there, visitors could one day watch aircraft operations or participate in spotting events.

The terrace extends nearly the entire length of the terminal, offering views of both northern and southern piers. However, the most spectacular perspectives — the panoramic views from the roof — remain inaccessible to the public.

Fig. 7. View of the main terminal.

Fig. 8. Observation deck, view towards the northern pier.

Commercial spaces and delayed opening

The airport was designed with a strong focus on non-aeronautical revenues and the demand for commercial space. Shops, cafés, and rental areas occupy multiple levels — opposite the arrivals zone, within departure lounges (both before and after passport control), and on the third level overlooking the check-in area. This upper level was meant to host travel agencies, cafés, and retail outlets.

Several of these premises were tailor-designed for specific tenants. By the time of the first planned opening, furniture and equipment had already been installed, and many entrepreneurs suffered significant financial losses when the launch was postponed. While large retail chains could afford to wait, for small businesses the uncertainty and delay proved devastating — some went bankrupt before the airport ever opened its doors.

The fire protection system

Officially, the repeated postponements were blamed on the fire safety system, which failed final certification. However, subsequent inspections revealed that many engineering systems — electrical, mechanical, and digital — were improperly installed, malfunctioning, or not synchronized with one another.

These discoveries exposed a severe lack of coordination and quality control within the project’s management structure. As investigations unfolded, political and corruption scandals erupted, further damaging public trust.

Fig. 9. Duty-free area before passport control.

One of the key design errors was attributed to the architects, who had proposed a smoke extraction system that would draw smoke downward through the underground levels, rather than upward via natural convection. It turned out that the engineer responsible for the system lacked sufficient experience to handle such a complex task.

During testing, smoke began to accumulate inside the building, revealing fundamental flaws in the design. As a result, numerous systems had to be rechecked, redesigned, or entirely replaced, inevitably leading to new costs and years of delay.

For example, after electrical plans were revised, kilometers of cables had to be reinstalled. Software for check-in and other electronic systems required constant updates and retesting. Much of the equipment purchased by shop tenants is now obsolete or expired. Even the flooring in the baggage hall must be replaced, as it failed to meet the required wear-resistance standards.

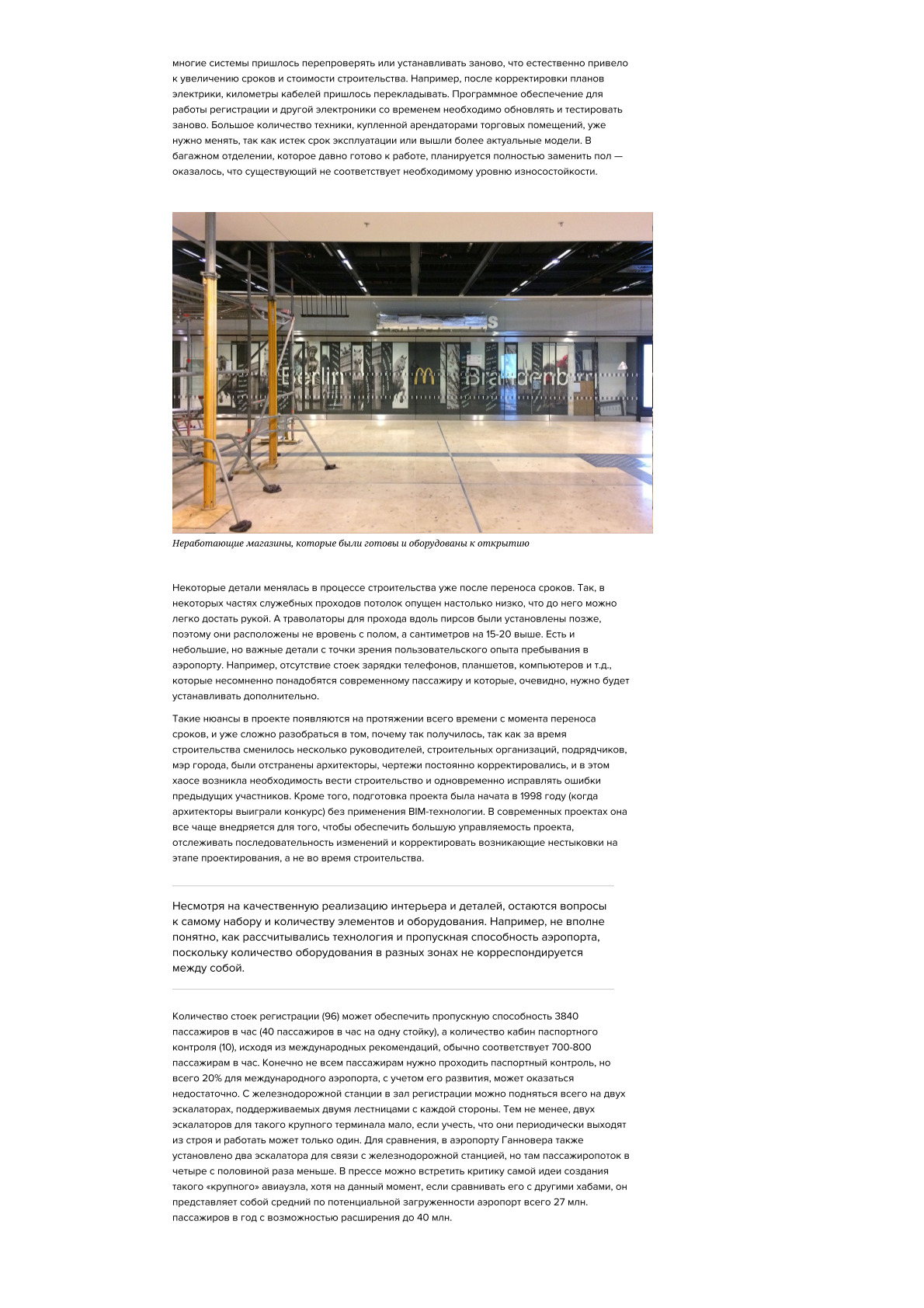

Fig. 10. Closed retail units that were fully equipped and ready for the opening.

Construction corrections

Some changes were made after the original opening date had already been postponed. In certain service corridors, for instance, ceilings were installed so low that one can easily touch them by hand. The moving walkways along the piers were added later and ended up being 15–20 centimeters higher than the floor, disrupting accessibility.

There are also small but critical user-experience flaws: the absence of charging stations for phones, tablets, or laptops — an essential feature for modern travelers — shows how quickly technology and expectations have evolved during the airport’s long delay.

Such inconsistencies accumulated over time, making it increasingly difficult to trace their causes. Over the years, the project saw multiple leadership changes — new managers, contractors, and design teams followed one another; even the mayor of Berlin changed. Architects were dismissed, drawings constantly revised, and the team was often forced to build and fix errors simultaneously.

Another fundamental problem lay in the project’s outdated planning methodology. The competition for the airport was won in 1998, long before the wide use of BIM (Building Information Modelling) technologies. In modern projects, BIM ensures greater transparency and coordination, allowing inconsistencies to be detected and resolved during design, not during construction — a tool that could have prevented many of Brandenburg’s costly errors.

Engineering Imbalance

Despite the high-quality interiors and craftsmanship, the balance between architectural beauty and engineering logic remains questionable. Some technical systems appear poorly correlated with actual passenger flow and operational needs.

For example, the 96 check-in counters can handle approximately 3,840 passengers per hour (assuming 40 passengers per counter per hour), while the 10 passport control booths, according to international standards, can serve 700–800 passengers per hour. Even allowing for the fact that not all passengers require passport control, this capacity — only about 20% of total throughput — may be insufficient for an international hub.

From the railway station, passengers can reach the check-in hall via two escalators, each paired with a staircase. For such a large terminal, this number is surprisingly low, especially considering that escalators frequently require maintenance and sometimes only one is operational. For comparison: Hanover Airport, which has roughly four and a half times less traffic, operates with a similar setup — a mismatch that points to underestimation of passenger volumes.

Operational logic and long-term delay

Fig. 11. Moving walkway in the boarding gallery of the southern pier.

Even the aircraft circulation system on the apron has raised questions. For several routes, aircraft cannot always be directed to the most convenient runway for take-off. For example, a plane bound for an eastern destination may have to take off to the west and then turn in the air, and vice versa. Technically, such situations could be avoided by routing aircraft to more suitable runways, but airport management decided that it would be more cost-efficient to manage these maneuvers in the air rather than on the ground, since aircraft consume more fuel while taxiing.

Years of inactivity brought other unexpected challenges. The maintenance company began reporting incidents of urban explorers (“stalkers”) sneaking into the empty terminal through the railway tracks, attracted by the thrill of exploring an abandoned site. As a result, the airport had to hire permanent security to prevent unauthorized access to the building.

Among professionals, opinions about the project vary widely. Some argue that it would be cheaper to abandon and rebuild the airport from scratch than to continue fixing its flaws. Others believe that once it finally opens, public perception will quickly change — much like with Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie, which also suffered a decade of delays but is now celebrated as a national icon.

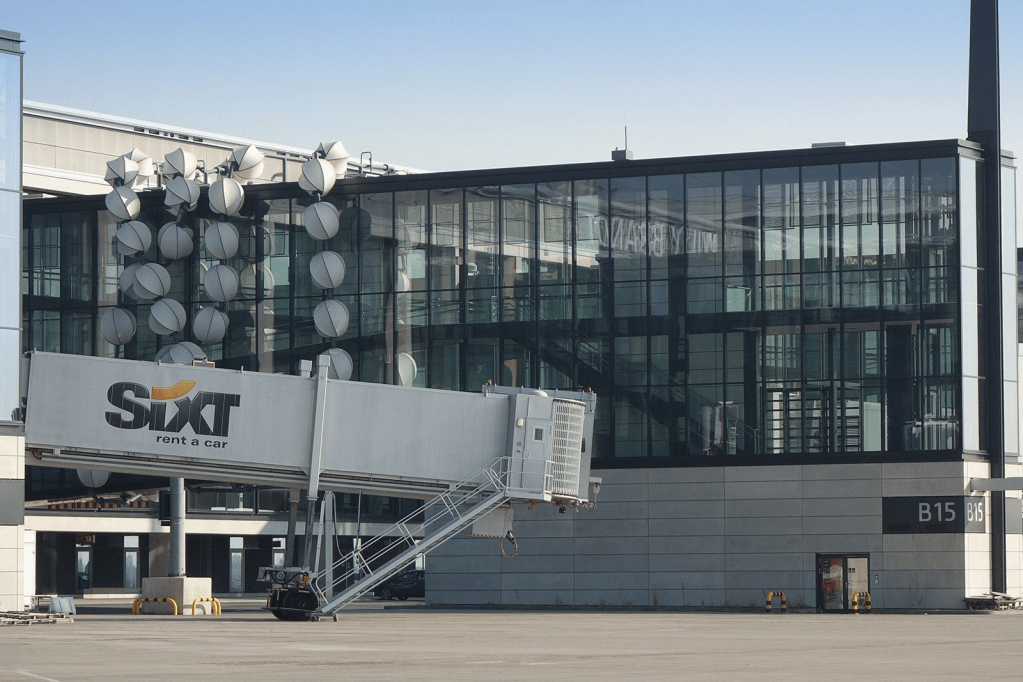

Fig. 12. View of the terminal from the apron.

A project between perfection and paralysis

From the outside, the terminal appears beautiful, solid, and perfectly executed. Yet inside, it remains unfinished, burdened by inconsistencies and bureaucratic complications. No one dares to predict with certainty when — or even whether — the airport will be fully operational.

Legally speaking, the airport is no longer considered a construction site. According to official representatives, September 2019 was set as the next date for testing all airport systems. If successful, a gradual six-month commissioning phase was planned, bringing the new projected opening to 2020.

Despite this uncertainty, long-term plans already include the construction of a second terminal (T2), to be located opposite the existing one and completed around 2024–2025. It is expected to allow the closure of the outdated Schönefeld Airport, taking over its passenger traffic entirely. The central square in front of the terminal is also planned to become a multifunctional public space, similar to that at Munich Airport. Munich, Germany’s second-busiest hub after Frankfurt, was even considered as a model of management for Berlin — its executives were invited to join the project, though no agreement was reached.

Maintenance and the present condition

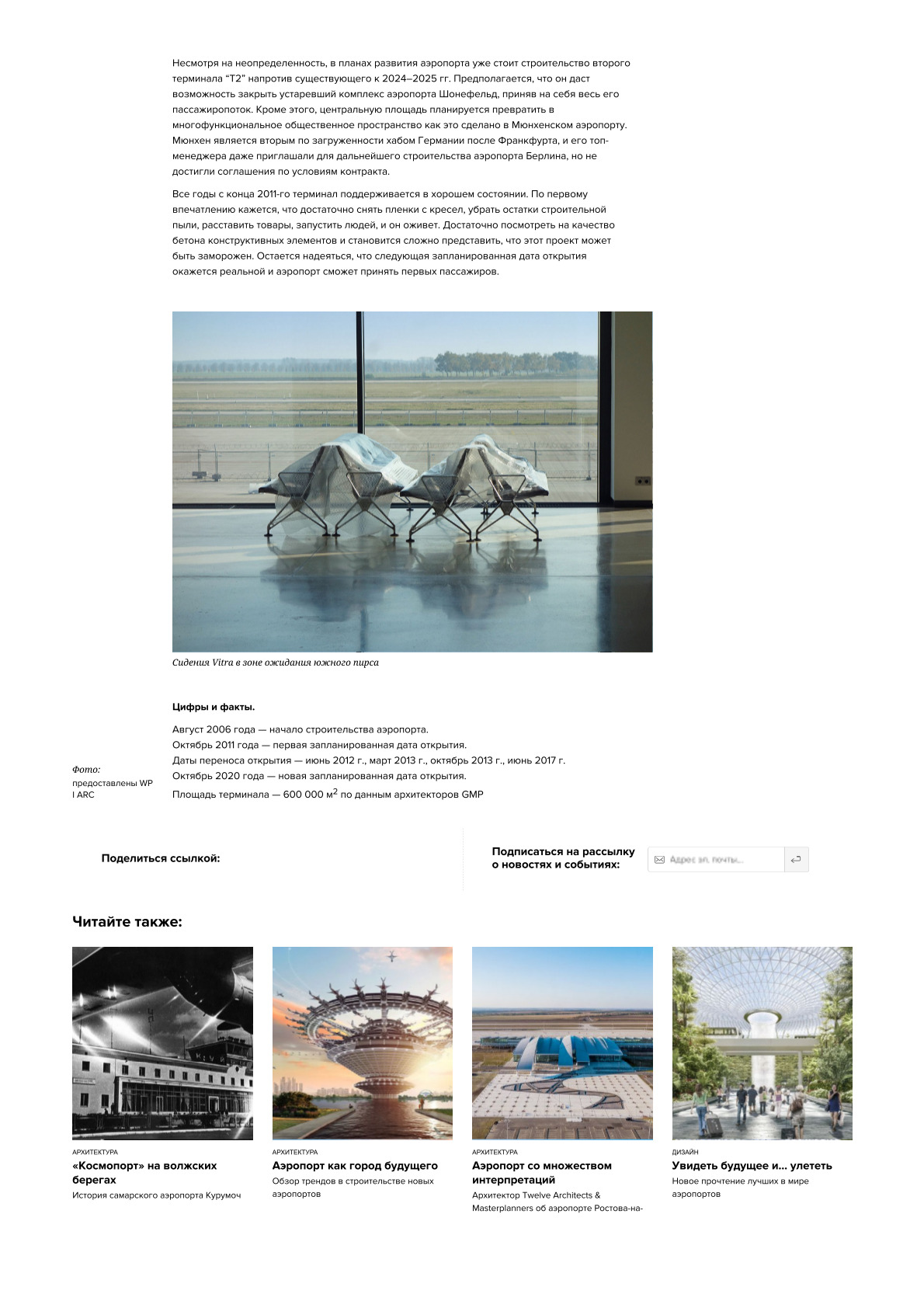

Since the end of 2011, the terminal has been carefully maintained.

At first glance, it gives the impression that the airport could start operating within days:

remove the protective plastic from the seats, clean away the remaining dust, restock the shelves — and it might come to life.

The quality of the concrete structures is remarkable; looking at the precision of the detailing, it is difficult to believe that such a project could ever be abandoned.

For now, however, the airport remains suspended in time — complete in appearance, but incomplete in function.

Optimists hope that the next official opening date will finally prove real and that Berlin Brandenburg Airport will soon welcome its first passengers.

This marks the end of “Architectural Triumph, Engineering Failure” — a story that captures both the ambition and the fragility of large-scale infrastructure projects.

Berlin Brandenburg Airport remains a powerful reminder that perfection in architecture means little without precision in engineering and management.

Fig. 12. Vitra seating in the waiting area of the southern pier.

Facts and Figures

- August 2006 — Construction of the airport begins.

- October 2011 — Initial planned opening date.

- Postponements: June 2012, March 2013, October 2013, June 2017.

- New planned opening date: October 2020.

- Terminal area: 600,000 m² (according to GMP Architects).

Photos: courtesy of WP | ARC

The full text is published in TATLIN journal (in RUS).